Advance Reserved Seating Tickets: $59 1st Tier; $49 2nd Tier; $39 3rd Tier; $29 4th Tier + applicable fees. Lincoln Theatre Members receive $2 off all ticket tiers.

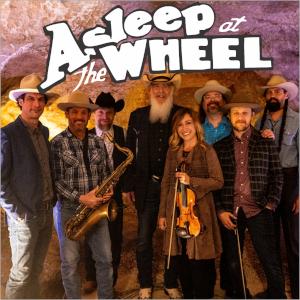

ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL

Fifty years ago, Asleep at the Wheel’s Ray Benson wrote in his journal that he wanted to form a band to bring the roots of American pop music into the present. It seemed like an ambitious goal for a 19-year-old, yet Benson has done exactly that -- traversing the globe as an ambassador of Western swing music and introducing its irresistible sound to generation after generation. Although the lineup has changed countless times since its inception, Benson’s mission has never wavered.

That merging of past and present is effortlessly woven throughout two of the band’s new releases. First, their Better Times EP compiles three new tracks: “All I’m Asking,” a rousing plea for a second chance; the hopeful title track, about getting back to life as it once was (namely, before the pandemic); and “Columbus Stockade Blues,” a traditional tune arranged in the spirit of Willie Nelson and Shirley Collie’s 1960s version. Then, in the fall, a career retrospective recorded with the new band -- and a few special guests -- will carry Asleep at the Wheel back onto the road, where they’ve remained a staple for five decades.

“I’m the reason it’s still together, but the reason it’s popular is because we’ve had the greatest singers and players,” Benson explains. “When someone joins the band, I say, ‘Learn everything that’s ever been done, then put your own stamp on it.’ I love to hear how they interpret what we do. I’m just a singer and a songwriter, and a pretty good guitar player, but my best talent is convincing people to jump on board and play this music.”

Raised in Philadelphia, Benson dropped out of college in 1969 and moved to a farm near Paw Paw, West Virginia, to figure out how to put a band together with two friends, Lucky Oceans and LeRoy Preston. Although he gravitated toward honky-tonk and swing music, Benson stood on the opposite side of the generation gap -- a young man opposed to the Vietnam War.

“Music became a rallying cry for these disparate groups,” he recalls. “My reaction was we need to take this music to my generation to show them it’s not the political posturing that is important, it is the soul of the music.”

Then, in 1970, two hippie buses pulled up to the farm looking for the band they’d heard about. Inside were a ragtag group of musicians calling themselves the Medicine Ball Caravan and they invited Asleep at the Wheel to open their upcoming show in Washington D.C. The fledgling band at this time was centered around guitar, steel guitar, bass and drums.

From that very first out-of-town gig, Asleep at the Wheel steadily built a fan base in D.C., and opened a date for Poco a short time later. However, Benson observes that the reception back home wasn’t always so warm. “We would play these little bars in West Virginia, and they thought because we were hippies, we wouldn’t fight. I stared down a few shotguns,” he says. “I think it was the music that saved us because we were playing real country music.”

When Benson booked Commander Cody for a double bill in D.C., the cosmic country legend encouraged them to give the Berkeley, California, a try. The group arrived out West in August 1971 and started booking shows in the East Bay clubs. Word of their Tuesday night gigs reached Van Morrison, who loved country music and asked to play a show with them. Around this time, when Rolling Stone asked if that pop star was excited about any new bands, he name-checked Asleep at the Wheel. That’s when, as Benson remembers, “the L.A record companies came running.”

Then everything happened fast. The band paid its dues by touring as country singer Stoney Edwards’ band in 1971. A year later, their United Artists debut album sold well in Oklahoma and Texas. In February 1973, they moved to Austin, Texas, encouraged by Doug Sahm and Willie Nelson; that same day, Epic Records issued the band’s second album. When that deal unraveled, they joined the Capitol Records roster.

One of the band’s compositions, “The Letter That Johnny Walker Read,” became a national Top 10 country hit in 1975. For the remainder of the decade, Asleep at the Wheel rode the wave of success, charting multiple singles and developing an international following. The Academy of Country Music named them the top touring band for 1977. The band won the first of 10 career Grammys in 1979.

“We’ve always said that we’re a live band,” Benson emphasizes. “We’ll make great records but it’s all about being on stage. The best promotion for a band is a great live show.”

By 1981, the band faced a turning point. Most of its members had departed and the disco craze stood in direct contrast to Asleep at the Wheel’s authentic approach. While the band still played shows, they went without a label deal for six years.

Benson made ends meet by producing commercials for Budweiser.

“The one reason that I kept going,” Benson says, “is that every week a fan would come up and be so appreciative, saying, ‘Don’t ever stop.’ We weren’t drawing a lot of people, but they’d say, ‘You’re the only band that goes out on the road and does this old, cool music.’ That’s when I knew it was more than just a living -- that I was blessed with caretaking a form of music.”

The 1990s put Asleep at the Wheel back on the map permanently, with the band regularly playing between 180 and 200 dates a year. Benson enlisted the top country artists of that era for an outstanding pair of Bob Wills tribute albums, a move that solidified the band’s focus on Western swing. When a duet version of “Roly Poly” with Dixie Chicks impacted country radio in 2000, Asleep at the Wheel became that rare country band to chart across four consecutive decades.

Fifty years in, Asleep at the Wheel represent an important cornerstone of American roots music, even though some of its members and audiences represent a new generation. That far-reaching appeal remains a testament to Benson’s initial vision.

“How do you keep this music going?” Benson asks. “Well, you’ve got to have some young people. If young people aren’t doing this, then we’re just a museum -- and I don’t want to be a museum.”